How a handful of animal lovers changed the world for homeless pets

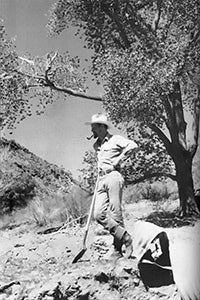

On a cold February day in 1984, a team of friends that would go on to be among the founders of Best Friends Animal Society, arrived at Angel Canyon and began clearing sagebrush for our first construction site. We called that first building the Bunk House, because that’s where we, the work crew, would eventually sleep. Paul Eckhoff, the trained architect among us, camped on-site in a drafty old travel trailer for a couple of days. In the mornings, his boots were frozen to the trailer floor and had to be cracked loose before he could put them on and start the day. The rest of us shared a rental in town.

On a cold February day in 1984, a team of friends that would go on to be among the founders of Best Friends Animal Society, arrived at Angel Canyon and began clearing sagebrush for our first construction site. We called that first building the Bunk House, because that’s where we, the work crew, would eventually sleep. Paul Eckhoff, the trained architect among us, camped on-site in a drafty old travel trailer for a couple of days. In the mornings, his boots were frozen to the trailer floor and had to be cracked loose before he could put them on and start the day. The rest of us shared a rental in town.

I know it sounds like one of those geezer stories in which the teller used to walk to school uphill in the snow both ways, but there we were, making it up as we went along. Among us, we had three old trucks, some hand tools, a map, a generator, a few dogs and some “how-to” books. Ironically, of course, there was no how-to manual for what we would ultimately create. It was the beginning of an adventure, and 35 years later that adventure is still unfolding.

Best Friends Animal Society is born

During those initial months, other colleagues arrived and, with them, about 200 cats and dogs who we had individually and collectively rescued out of various shelters or from some lonely highway. Eventually and majestically, the sanctuary that we had imagined — the vision of which guided us through those early days — became a reality and Best Friends was born.

Thinking back to that time, however grandiose our flights of fancy, we could never have imagined how the simple and seemingly obvious idea that homeless pets should be saved rather than killed would change the world of animal welfare and propel our harebrained undertaking in the middle of nowhere to international prominence.

More about Best Friends no-kill initiatives

Grow, adapt, evolve

We weren’t initially planning on it, but a few months in, to address a situation of abuse and neglect at the local pound, we asked the mayor of Kanab if we could take on animal control duties for this small, rural community. After all, we reasoned, how difficult could it be?

We weren’t initially planning on it, but a few months in, to address a situation of abuse and neglect at the local pound, we asked the mayor of Kanab if we could take on animal control duties for this small, rural community. After all, we reasoned, how difficult could it be?

The existing pound was a depressing three-sided cinder-block structure divided into four or five sections with some fencing and a corrugated steel roof. It was punishingly hot in the summer and frigid in the winter. Once a week, a vet would make the hour-and-a-half drive from St. George and kill any dogs unlucky enough to find themselves in this small compound, which resembled something out of a World War II concentration camp. (They did not house cats there.)

We knew that anything we could do for these poor animals would have to be better than that fate and, of course, we had no intention of killing any animal in our care.

That was the first of many occasions in the following years (and up to the present day) that the real-world needs of homeless pets, beyond the idyllic confines of our red-rock canyon sanctuary, required us to make dramatic changes to our operation and to our own ideas about the role of the Sanctuary.

It wasn’t long before one of the founders, Faith Maloney, became the de facto animal control officer for three area counties, and the rhetorical question “How difficult could it be?” was answered as our population of rescued animals grew from 200 to 500 to 1,000 to 1,500. Whatever ideas we might have had about easily managing the local homeless pet population gave way to the urgent demands imposed by the sheer number of animals in our care.

The scale and scope of our responsibilities — physically, financially and emotionally — were no longer being managed according to our predetermined plan. We were now operating at a pace determined by the sad reality of animal control and the long-standing practice of killing pets in America’s shelters. Suddenly, no-kill became more than simply the way we operated our own growing Sanctuary. It became the flag that we flew and the course that we would chart.

We had to grow, we had to adapt, and we had to evolve.

Pushing the envelope and leading the way

Over the years, the Sanctuary has continued to evolve in what we do and how we do it, as a function of the changing landscape of animal welfare in the wider world. As a beacon and a laboratory for the no-kill movement, the Sanctuary challenged convention in animal care protocols in terms of what constitutes an adoptable animal and many of the rationales that were being used to justify the killing of dogs and cats in shelters. For example, early on, we had the largest population of otherwise healthy cats with feline leukemia (FeLV), who we kept well through proactive care and support. And we worked with universities on field trials of some of the early FeLV in-house screening tests.

Over the years, the Sanctuary has continued to evolve in what we do and how we do it, as a function of the changing landscape of animal welfare in the wider world. As a beacon and a laboratory for the no-kill movement, the Sanctuary challenged convention in animal care protocols in terms of what constitutes an adoptable animal and many of the rationales that were being used to justify the killing of dogs and cats in shelters. For example, early on, we had the largest population of otherwise healthy cats with feline leukemia (FeLV), who we kept well through proactive care and support. And we worked with universities on field trials of some of the early FeLV in-house screening tests.

In 1987 when feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) was identified by a researcher at the University of California, Davis, we tested cats from one of our areas with cats living together and learned that about half of them had FIV. On the advice of the team from UC Davis, we kept this group isolated and neither adopted out cats from this group nor added any new cats to live with them. Several years later, we retested all of FIV cats appearing outwardly happy and healthy, and to everyone’s surprise, all of them who had previously tested negative had not contracted the virus.

Thanks to the Sanctuary’s commitment to the lives of all our cats, we demonstrated quite by accident that FIV is not spread easily. And as other university researchers later confirmed, it is most commonly transmitted via bites when cats fight. That bit of information has spared the lives of untold numbers of FIV cats previously being killed in shelters.

Saving animals from disasters and abuse, supporting shelters

Landmark events such as Hurricane Katrina, the Vicktory dogs (the name we gave the group of dogs rescued from Michael Vick’s dogfighting ring) and Hurricane Harvey pushed the envelope of the Sanctuary’s operations in significant ways, but none more so than the incremental changes required to stay in sync with Best Friends’ growing national reach.

Again, our plan, such as it is, has always been to save animals’ lives. Whether that has meant Faith going on every local police call back in the 1980s that involved a dog or cat, or turning Dogtown inside out to create special accommodations for the Vicktory dogs, or working to achieve no-kill nationwide by 2025 by implementing new health and behavior protocols, the Sanctuary’s north star has remained the same.

Today, the Sanctuary is adapting to support Best Friends’ no-kill campaign by providing support for our regional operations in Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, New York and Houston, as well as in places like Edinburg, Texas, and other border communities where tens of thousands of pets are killed annually.

The Sanctuary, though, does much more than save at-risk animals: It transforms people’s lives.

More than a set of buildings

The power of Best Friends’ no-kill philosophy, the magical beauty of the canyon and the miracle of love that is expressed in the lifesaving kindness and care of our staff has made the Sanctuary a mecca for animal lovers everywhere. In 2019, more than 30,000 visitors will experience the Sanctuary. They will be inspired and revitalized in their commitment to the animals and the no-kill movement. It is an indelible, life-changing experience.

None of us who were there on Day One 35 years ago with cold fingers and toes and chattering teeth, had any idea what lay ahead. To be honest, however much we may think that we have the Sanctuary operation locked in, I know that it will change and grow because it is so much more than a set of buildings. It is a living, breathing thing.

Best Friends Animal Sanctuary is the beating heart of our organization. That’s what it has always been and that’s what we intend it to remain. It inspires me every day, as it has inspired hundreds of thousands of visitors over the years as we move closer to realizing our mission to bring about a time when there are no more homeless pets.

This article originally appeared in Best Friends magazine. You can subscribe to the magazine by becoming a Best Friends member.

Photos by Best Friends staff