Helping animal shelter staff handle disease outbreaks

They called him Dude. And in his own way, the chunky, gray-and-white dog, sitting peacefully amid all the commotion outside his kennel, epitomized cool. He was one of approximately 700 dogs in a Texas shelter suddenly placed in harm’s way by an outbreak of distemper. The Dude appeared unruffled as nearby vet techs swabbed, tested, and separated dogs in an effort to isolate those possibly infected from those who were not.

Canine distemper, a highly contagious and potentially fatal disease in dogs, is a nightmare for any animal shelter. Because the virus is in droplets transmitted when infected dogs in close proximity bark, sneeze, or cough, a single case can spread quickly and easily. For many years, a distemper outbreak meant many deaths for animals in shelters. But today, new proven shelter medicine strategies — biosecurity, tests, treatments, and moving animals as fast as possible through the shelter system to minimize exposure to illness and stress — can transform a dire situation into a lifesaving effort.

[Watch a dog’s first day out after surviving distemper]

With most shelters lacking the resources or a medical team that is experienced in outbreaks, they often must seek outside help. The Best Friends national shelter medicine team is set up to assist in just such situations, so shelters have an alternative to “depopulating,” or killing animals who might have been exposed to the disease. The team, which provides free, remote or hands-on assistance and consulting services to shelters across the United States, is one of the ways that Best Friends is helping shelters reach no-kill in 2025.

“Our team’s scope of work might look different depending on whether a shelter just needs remote consulting or if we send staff to a shelter to oversee an effort,” says Dr. Erin Katribe, director of Best Friends’ national veterinary programs. “Or it might involve just adding manpower to help with diagnostic testing or other labor-intensive work to help an already overburdened shelter suddenly faced with an outbreak.”

The national shelter medicine team has dealt with all kinds of outbreaks that impact dogs and cats in shelters: distemper, panleukopenia, parvovirus, canine influenza, and others. In addition, the team provides training for veterinarians and their staffs on high-quality, high-volume spay/neuter, and it also works with Best Friends’ national shelter support team to help shelters improve their overall lifesaving efforts through animal care and veterinary programs.

Road warriors

Helping various shelters with outbreaks large and small requires significant time on the road. “It’s five of us — three veterinarians, two technicians, and we travel all over the country at least 50% of the time,” says Dr. Becca Boronat, national shelter medicine team member. “We have shelters who reach out to us directly for help, or they might contact us through the shelter medicine section of the Best Friends website.”

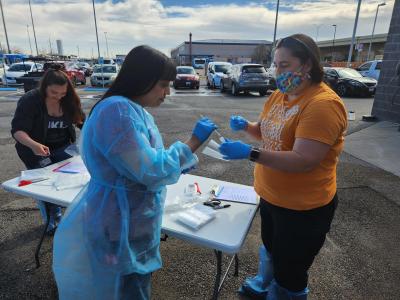

Assistance provided might be as simple as a one-hour virtual consult with vet techs, or it could be something more in-depth — for example, gearing up for a potential outbreak. Sometimes that could mean sending in Best Friends vet techs or veterinarians to organize the response.

“It all depends on the situation and the need,” says Dr. Erin. “And sometimes geography plays into it. I’m based out of Houston, and so I have visited many shelters in the Houston area. It’s easy for me to pop over when they’ve had disease issues.

“Sometimes we’ll do a site visit to get the lay of the land and then follow up remotely with staff. Other times, we may already have a Best Friends person embedded with a shelter’s staff. It can be anything — from a 100% virtual consultation to a quick check-in to having a staff member on-site for an extended period of time.”

All hands on deck in Texas

Best Friends employees Nicole Wisneskie and Emily Lancione, embedded with the Texas shelter staff on assignment through Best Friends’ national shelter embed program (made possible in part by a grant from Maddie’s Fund®), were reviewing the shelter’s data when something caught their attention. “We noticed that a lot of animals seemed to be dying of upper respiratory illness,” says Nicole. “That got us to thinking that we might be dealing with something pretty serious.”

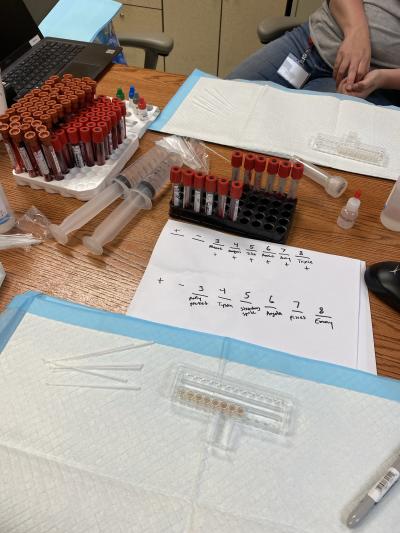

So, by the time Dr. Erin arrived at the shelter for routine consultation as part of the embed agreement, everyone was on the lookout for a possible outbreak. Testing confirmed not only cases of distemper but also strep zoo, a bacterium that can cause severe pneumonia in immunocompromised dogs.

“The shelter staff was understandably a bit nervous at first,” says Nicole. “But Dr. Erin was so helpful through the whole thing. She has such a calm presence, and everything is approached 1-2-3 in a very logical manner. Her leadership was key. It not only made Emily and I feel better, but it made the shelter’s staff feel better, too.”

[Love and expert care: Saving puppies with distemper]

Dr. Becca says dealing with an outbreak is as much about working with people as it is working with the animals. “In addition to paying attention to the animals, we must be really careful to help a shelter staff go through the process,” she says. “Sometimes protocols that are supposed to be followed have not been happening, and sometimes a person will think ‘Oh, it’s my fault.’ But we don’t want to blame anybody.”

“Treating people well is important in everything we do,” says Dr. Erin. “It’s just letting folks know that they are not alone and that your shelter is not the only one this has happened to. They need to know we will get to the other side and that we as a team will absolutely help you do that.”

There’s also the sheer physical work required during an outbreak. “It’s physically exhausting,” says Emily. “The PPE (protective equipment) that you have to wear while handling the dogs — you know, those white COVID-style jumpsuits? You have to change suits between each animal, and sometimes one animal is tested several times in a day.”

Setting up a shelter for future success

Convincing shelter management that changing a routine will help them get through the crisis can sometimes be a challenge, Dr. Erin says. “Oftentimes we will recommend stopping animal intake until we can work through the outbreak, but that can be really scary for shelter directors. Or it may seem very difficult because they’ve never done it before. But that’s our role — to give our best advice.

“They might not follow our recommendation to the letter in every case, but in the vast majority of situations, we can come up with solutions that will work. We have to be able to adjust things because not every shelter has all the resources available. We just help them do the best they can with the situation they are in.”

Outbreaks of disease are hard, says Dr. Erin, but one of the positives that emerge is the opportunity for a shelter to do a reset. “Outbreaks are difficult for the shelter, the staff, the community, and the animals. But sometimes we are able to leverage that outbreak to create lasting change,” Dr. Erin says. “We know the conditions that lead to outbreaks, including things like overcrowding, so we try to the best of our ability to help a shelter prevent it from happening again.

“When you are in the midst of the outbreak, it’s hard to think about that stuff. But working through one and getting to the end of it gives you a chance to really consider improvements for the future.”

The Dude is emancipated

It was during the beginning of testing that Nicole and Emily first noticed Dude — all 60 pounds of him. And although the big fellow was cleared after testing, he had to be isolated from all the other quarantined animals. Figuring in the fact that Dude had already been previously quarantined for another issue, the poor guy had been cooped up for almost two months.

“There was nowhere to move him,” says Emily. “Everything was shut down, so no animals were moving anywhere. So there he sat. The good news is within a matter of weeks we were able to get the kennels open and get the dogs (including Dude) out again."

But there was even better news. Once the situation at the shelter had eased, a family came by and adopted Dude. “He was a crusty guy with a few skin issues,” Emily says through a smile. “But he was as nice as ever … a good boy.”

Let's make every shelter and every community no-kill by 2025

Our goal at Best Friends is to support all animal shelters in the U.S. in reaching no-kill by 2025. No-kill means saving every dog and cat in a shelter who can be saved, accounting for community safety and good quality of life for pets.

Shelter staff can’t do it alone. Saving animals in shelters is everyone’s responsibility, and it takes support and participation from the community. No-kill is possible when we work together thoughtfully, honestly, and collaboratively.