A Tribute to Gregory Castle

This is tough. Gregory and I were friends, comrades and colleagues for over five decades. We knew each other long before Best Friends, we ran a jazz club and coffeehouse together in Chicago, we went to Dolphins games at the original Orange Bowl in Miami, caravaned from New York City to Arizona where the seeds of the sanctuary were sown and broke ground at Angel Canyon along with other founders in 1984. Gregory, Julie, and my wife Silva and I traveled together across the southwest, Europe, and Hawaii. He was my friend, my fellow adventurer, and one of the most quietly extraordinary people I’ve ever known.

Digging around in my memories to do justice to the man also brings to mind the many things I wish I had said to him while he was with us, but there is no point in regret.

Gregory was never the loudest voice in the room, but always he was one that you listened to. His legacy is enormous. If you knew him personally, you know that what made Gregory unique wasn’t just what he accomplished — it was how he was.

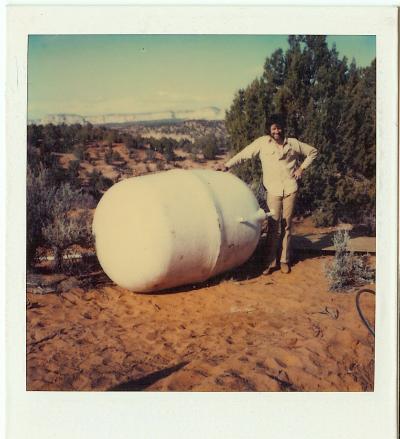

For 41 years, Gregory lived and worked in the red rock canyons of southern Utah, where he helped build Best Friends Animal Society from the literal ground up. He ran electric lines and plumbing through the canyon by hand, guided by a stack of do-it-yourself manuals. That always struck me as so Gregory — a Mr. Magoo level of confidence taking on tasks that he had no preparation for, like hooking up 10,000-volt transformers when we were building the sanctuary with just a 10’ insulated pole, a pair of heavy gloves and rubber soled shoes! In the words of a ditty from another era, it was a case of “Mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun.” Gregory was definitely very much an Englishman and, like the rest of us, something of a mad dog. Capable and undaunted, he didn’t talk about it much. He just did it. And that was just the beginning.

In 1991, when the smelly stuff hit the fan and we had to figure out how to support the 1,500 or so animals that we had rescued, Gregory set about building programs and a support base in Salt Lake City, while Silva and I decamped for Los Angeles.

Again, with no apparent qualifications other than a very toney British accent, Gregory aimed high and succeeded. Within a few years, he created Utah’s Week For The Animals, a statewide celebration that included a K-12 humane education curricula, student art competitions, special classroom activities and adoption events.

It was while building our Utah programs, that Gregory met and eventually married Julie Stuart, a team-up that would change the course of Best Friends and of animal welfare forever, when, in 2000 they launched an audacious campaign, with a multimillion-dollar grant from Maddie’s Fund, to make Utah a No-kill state. Maddie’s was a start-up at the time with an endowment from PeopleSoft founder Dave Duffield and led by Rich Avanzino considered by many to be the father the of the no-kill movement. Gregory worked with Rich to create a template for collaborative success that would later be replicated in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

Gregory served as CEO of Best Friends from 2009 to 2018 — a period when the organization was growing rapidly and needed a steady hand. When the board of directors turned to him and asked him to step into the CEO role, Best Friends was in transition. Gregory was the perfect choice to guide the organization forward. He brought stability and structure and a focus on Best Friends mission. He did what he always did: he brought order, calm, and clarity.

He helped lay the foundation for what Best Friends is today — the national leader of the no-kill movement, working toward a future where every animal is safe and loved. Gregory had the rare gift of being both visionary and pragmatic. He didn’t just dream of a better world for animals — he helped pull together disparate programs, bring already great work into focus and helped lay out a plan of how to build that future, brick by brick. And he did it with kindness.

Gregory’s roots were in England — born in Cranbrook during WWII, raised in Folkestone, a coastal town on the English Channel, hit hard during the war. His father, Norman, was a civil engineer who stayed behind to serve while most of the town was evacuated. For his work, Norman was awarded an Order of the British Empire. That quiet bravery ran in the family.

Gregory went on to study civil engineering, philosophy and psychology at Cambridge, where he also joined the famous Cambridge Footlights — the same student comedy troupe that launched a generation of British acting talent including Monty Python’s Flying Circus. He dipped his toes into filmmaking, directing a 1961 film (The Connections) as a film photographer. But his life took a more spiritual turn — one that eventually led him to the American Southwest and a cause that would define him.

He was an early champion of animal welfare, helping unify grassroots rescue groups, shelters, and national organizations at a time when they rarely saw eye to eye. Gregory’s style wasn’t to shout slogans. He just got everyone in the room and said, “Let’s figure this out.” And they did. His list of accomplishments for the animals is too long to go into here, but noteworthy were his meetings with the President of Ethiopia to recommend an alternative solution to the proposed cleanup/culling of thousands of stray dogs in preparation for their national celebration of the Coptic Calendar Millenium in 2007. Gregory led a Best Friends team that brought in high volume spay/neuter vets and worked to divert a disaster for the animals.

As founders of Best Friends, we are often asked what we are the most proud of. Gregory answered that question by saying “I feel very proud of us I have personal pride in this and am incredibly lucky and blessed to have made this my life’s work — something that is really truly gut-real and meaningful to me… Looking back, I think, ‘Boy, what a gift to be given.’”

Gregory and I shared a lot over the years — long conversations, laughter, plenty of silence. He had that British “Keep Calm and Carry On” steadiness, I, a New York Italian was more combustible, but Gregory’s razor-sharp mind, a wicked sense of humor, and a deep well of compassion were complimentary to my hand-talking style. And bagpipes. Yes — he played the bagpipes. At one time, he played them every Sunday at dusk, by himself, standing on a cliff edge looking out over Angel’s Rest at the Sanctuary. It was a haunting sound. He said he played them for the spirits of the animals who were buried there. He played them at my wedding to Silva too.

He often called himself a “cat person,” but Gregory had a deep love for all animals. In the early days of Best Friends, he shared his living space with an impressive number of cats. Later, he added dogs to the mix — most notably, his beloved German Shepherds, Shadow, Sunny and Marley. They were rescues from Los Angeles, and they became his loyal running companions.

Running was another thing that defined Gregory. Over 20 years, he completed 17 marathons — including three Boston Marathons. And at 73, because of course he would, he became the oldest participant at the time in the Grand-to-Grand Ultra — a brutal 170-mile, seven-day race through Utah’s backcountry. “It was a real physical test,” he shared. “I had no idea whether I could do it. I’d run marathons, but six in a row? That was an experiment.” He talked about how serious runners often had a mantra. Three or four words they say during a race over and over again to give them strength. During a particularly challenging part of the race, after running through a rainstorm a thought came into his head that became his mantra: “This is nothing.”

Compared to the fate of animals dying without a home, he said, the suffering he was experiencing — blisters, exhaustion, dehydration — was nothing. “I was doing this for the animals,” he said. “That mantra kept me going. And sure enough, I finished. I think I came last.”

I don’t know anyone who would call that last.

For me, the loss is deeply personal. He was my friend — someone I admired, trusted, and could always count on for a thoughtful word. He made everyone feel a little calmer, a little clearer, just by being in the room. And his life — well, it spoke louder than any words ever could.

He changed the world. And he did it gently.

“I think of the lives we have saved,” he once said. We do too, Gregory. We always will.

-Francis

Gregory is survived by his wife Julie; his daughter Carragh; his granddaughter Zoe, his brother Christopher; sisters Jan and Susan, cats Ellie and Maggie, and dogs Sunny and Marley.