The dogs who shaped me

Some of my earliest memories are of sitting on the front-hall staircase of our little house in Mamaroneck, New York, with our dog, a sturdy mutt with a black saddle and ear patches. He was white with black spots on his muzzle, shoulders, front legs, and underside, which looked a bit like a royal robe, so he got the name Prince. He was always Princey to me.

He and I would sit waiting for my mother to return from shopping. He claimed the window seat, so he could stick his nose under the venetian blinds and watch for my mother walking in wind-up doll mode — a 4-foot-11-inch woman in low heels moving at speed with two large paper bags of groceries in her arms. Click, click, click. High-speed short steps. I could never keep up with her.

I would sit next to Prince on the staircase and hug him, telling him my problems — as if I actually had problems, but whatever they were, I shared them with him. To me, he was my dog, my confidant, and I was his boy. But in fact, he was my mother’s dog. He wouldn’t seem to be paying the least bit of attention to me when she was around; he was all about my mother. But just being with him made me feel good. So he did solve my problems.

Occasionally, my father would play grainy 8mm home movies (which he never seemed to tire of) featuring my older brother, my sister, and me with the dog who preceded Princey, chasing me around the front yard. I was 2 years old, waving a stick to entice the old girl, Foxy, to play. My father’s other fave was of me in diapers being chased by a goose at some summer cabin in Brewster, New York, cutting to me petting a cat and squealing with delight.

[Making a better world through kindness to animals]

All that is to say that animals have always been a part of my life and were always part of our family. When Prince died, I don’t know which was more difficult for the 10-year-old me to navigate — my own sadness and loss or watching my mother attempt to hide her grief and tears from me.

Like most of you reading this, I have been dramatically impacted by the animals who have come into my life over the years: how they entered, how they departed, and our adventures along the way. Too often, I only remember their last years and their struggle with whatever finally claimed them. I thin about what I might have done differently or am focused on their end-stage condition. That misses the essence of the animal and our years of a joyful relationship. So, with apologies to the hundreds of friends who won’t get a mention, this is a thank-you to some of the dogs who took on my care and training after Prince.

After Princey passed, we moved into a two-family home where we weren’t allowed to have a dog. The owners, who lived downstairs, barely tolerated the pitter-patter of the rescued kitty I brought home to my folks from college.

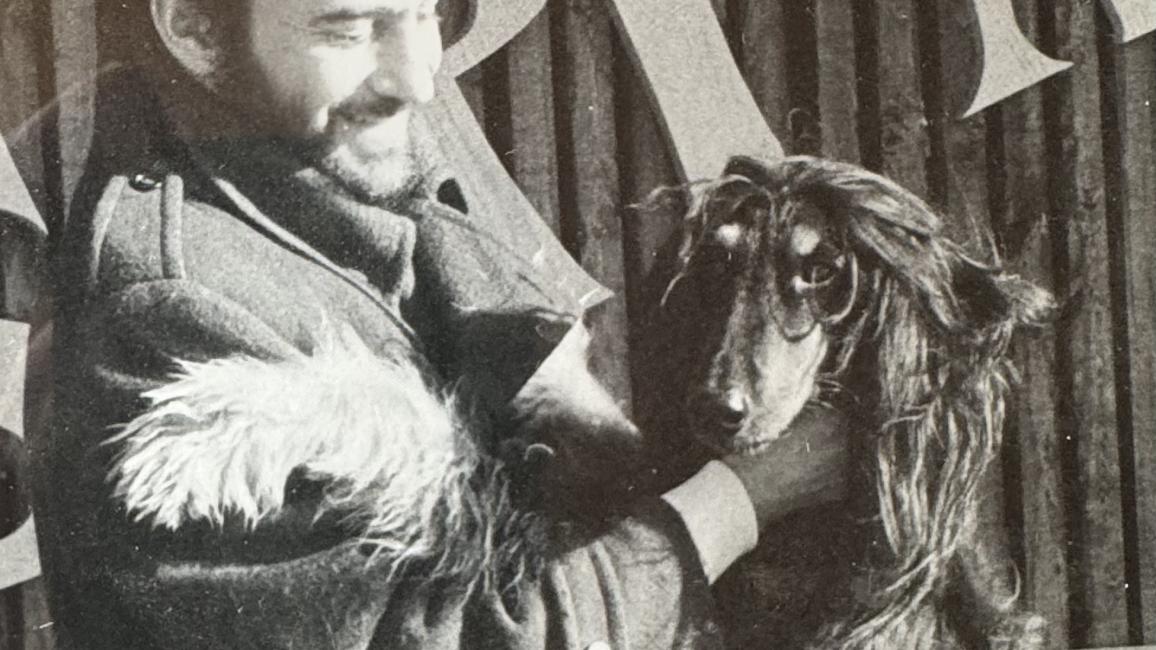

I looked after the dogs of various friends in the interim, but it wasn’t until 1974 that I adopted my first dog. Jasper was from a shelter in Miami, Florida, an old, rundown building typical of the era. I took a walk down the row of available dogs and came back to the front desk to ask a question when a guy walked in with a black-and-tan Afghan hound who was so matted and dirty that it was hard to tell what I was looking at. His front legs were attached to his hind legs by cords of matted hair; his coat, which should have been silky, was bunched up in pads; and his head seemed to have a felted crash helmet on it. His demeanor was so downcast that it was depressing.

The guy said that a hippie couple had left him behind when they went to the islands for a month. That was two months prior. The dog’s name was Sakyamuni, which translates from Sanskrit as Sage of Sages, better known as the Buddha. A heavily weighted name for such a sad sack, but time would show that he was at least a sage, if not the Sage of Sages. We decided to bypass the intake process, and the guy handed Saky’s lead over to me. Thus began a wonderful friendship.

I changed his name to Jasper and immediately removed what I could of his mats with scissors. He looked like a Dr. Seuss character. Jasper blossomed into a magnificent dog and traveled with me from Miami to Chicago, from Chicago to Toronto, back to Chicago, then to the New York City area, and finally out west to Arizona and then to Kanab, Utah, where he was among the dogs present at Best Friends’ groundbreaking day in 1984.

[The beating heart of Best Friends Animal Society]

In Miami, Jasper ran sports-field-sized circles in the park just to stretch his legs. In Chicago, he posed at sidewalk café tables and once confronted an escaping burglar with me in the middle of the night as I held him on a short lead as if restraining him from attacking. He was harmless, but I don’t think the burglar had ever seen such a creature and willingly emptied his pockets of the items he had lifted.

The irony here is that Jasper himself was a thief, the kind who leaves no trace and displays no guilt. I would sometimes leave a plate of food on the table with Jasper stretched out asleep in the corner. When I returned, the plate was placed neatly on the floor, and it was clean as a whistle. To all appearances, Jasper had not moved an inch. He had gently removed the plate full of food from the table and quietly placed it on the floor. The folks who claim that sight hounds are not very intelligent are just testing for the wrong skills.

Jasper was chill, graceful, patient, and as cool as a cat. He also had the uncanny ability to cure the blinding headaches I used to get. I would rest my head on his side for a quick nap — and headache gone.

By 1986, when he died of bone cancer, Jasper had ushered me down the aisle of total commitment to animal welfare. He was the first of our rescued sight hounds, followed by Afghans Lancelot, Junior, Sheba, and Buffy and racing greyhounds Jet and Tut, along with a whippet, Brodie. They all now rest at Best Friends.

On one cross-country trip in 1982 with fellow co-founder Faith Maloney and some dogs and cats from the little shelter she was running in New York state, we stopped for gas on the lonely outskirts of Deming, New Mexico. As I was pumping gas, I noticed something move behind a dumpster: a little blond dog. Because I had the regrettable habit of rescuing dogs who didn’t actually need rescuing, I checked with the gas station attendant, who said the dog had been cowering out there for a day.

Since it was now the next day and there wasn’t another building in sight, I offered her a piece of cheese and loaded her up to join our traveling menagerie. She was some kind of terri-poo — her front half silky and her back half kind of frizzed up like a poodle. She rode on my lap for the next eight hours and didn’t reveal her impish charm for a week or so. I named her Goldielocks.

Goldie joined me in Kanab as soon as we had some dog runs set up behind The Bunkhouse, where the advance team lived. I’ll never forget putting her in the back run that first day, walking through The Bunkhouse and out the front door only to be greeted by Goldie, who had scaled two 6-foot fences in the 20 seconds it took me to walk through the building.

After Jasper passed away, Goldie became one of a trio of dogs who rode around the canyon with me in my truck and then in an old jeep. Grelle, Zsa Zsa (aka ZZ), and Goldie were a great team. Grelle was a beautiful Belgian sheepdog who came to us from a local woman when one of her dogs ran afoul of her neighbors’ livestock and she had to downsize without notice. ZZ was one of several cattle dogs I took in from early Dogtown days. Each was smarter than the next.

They were my worksite buddies and the first of a gang of about 20 dogs who I cared for in my little corner of Best Friends and who spent the nights with me in the A-frame near Cat World. Sleeping in a hammock that stretched from one end of the little house to the other, I caught all the smells that the carpet of canines below, along with quite a few felines, could generate.

It helps to understand this apparent madness when you appreciate that the founders constituted a pressure release valve for Dogtown and Cat World, and our accommodations were an essential component of the growing sanctuary. Besides, my personal ethic had evolved to feeling that if I wasn’t being inconvenienced by animals in need, then I wasn’t trying hard enough.

When I sat down to write about how individual animals have touched my life and what I’ve learned from them, I realized that, after 40 years of animal welfare work and nearly double that of just living, I would need to write an entire book — and I still wouldn’t do all of them justice. For the animal lovers I’ve known, our pets represent the chapters in the stories of our lives. They are our traveling companions through different phases of our lives, but just as important, they have their own stories, the ones told through their eyes.

Even writing this, it feels wrong to leave out Billy and Jeffrey and Roxy and Dermott and Bismarck and Teddy and Q and Treat ... the list goes on. I have been very, very fortunate and rich beyond measure in my friendships. I have more stories to tell of the dogs and cats who were there for me in the story of my life — as I was there for the story of their lives. Perhaps I’ll pick up the thread down the road.

This article was originally published in the November/December 2024 issue of Best Friends magazine. Want more good news? Become a member and get stories like this six times a year.

Let's make every shelter and every community no-kill in 2025

Our goal at Best Friends is to support all animal shelters in the U.S. in reaching no-kill in 2025. No-kill means saving every dog and cat in a shelter who can be saved, accounting for community safety and good quality of life for pets.

Shelter staff can’t do it alone. Saving animals in shelters is everyone’s responsibility, and it takes support and participation from the community. No-kill is possible when we work together thoughtfully, honestly, and collaboratively.